Here is a story for you: Tom Simpson died at the age of 27 while racing in the Tour de France in 1967. Read just a tiny bit about him and you know that his story is about the body reaching its limits and him refusing to know them. The body does have limits. This is not news. We all know it. In old film footage, it is possible to see Simpson curving from one side of the road to the next, the crowd lining the street standing nearby, friends and medics rushing in. Finally, we see him fall and get a view of him being carried off by helicopter, out of his own internal chaos which was at full throttle with body giving out and mind going on, going on. The footage can be viewed here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtAyGvZqiwk.

And have you heard of the ballet Giselle? It holds the romantic’s version of this scene: Giselle dies because she can’t keep herself from dancing, or loving, despite a weakened heart. She must dance, in the same way that Simpson was compelled to keep riding his bicycle almost 100 years later. Giselle falls in love, is then betrayed by her lover, making her dance even more. Villagers gather around as her body fails her. Just before her collapse, she wavers dramatically across the stage, no longer dancing but stumbling, believing otherwise–just like Simpson…only with Simpson there is the terror of reality, his falling while famously saying, “go on, go on.” With Giselle, there is a rising from the grave–she succeeds in saving her lover from eternal condemnation by dancing from midnight until dawn for a dark hearted fairy queen. The premise is just short of ridiculous. I say just short because we know that there is the unstoppable in each us.

To watch even a few moments of professional cycling is to know that here is the body pushed to its extreme, here is the body in partnership with a very efficient machine that is the bicycle, here is the body looking to match angles, aerodynamics, grams, rigidness and flexibility of frame. The cycling body is never an illusion. It bears weight and power, kilojoules, and every kind of measurement one can imagine these days. It is never rising out of the mist, never looking to appear as if it is not bearing weight. Unlike ballet, races are won by fractions of seconds, there is a clear winner (although splitting seconds is not always so clear), and there is always the threat of crashing. Results are posted, finishes are exact, great rivalries are not hidden, whether gentlemanly or ferocious. The sport at its most extreme levels is unparalleled, its reality literally speeding by us on display.

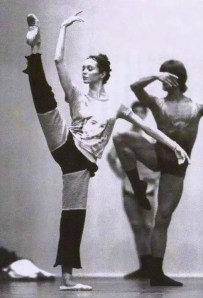

There is indisputably some of the same “go on, go on,” within ballet dancers, but a greater game of illusion. There is the same fire-playing with the limits of the body. But we can’t see very much about what it is to be a dancer, about what the dancer’s body lives, feels, breathes, weighs, thinks—there are no kilojoules and weight is a well kept secret despite its prominence as a topic of conversation, always around it but the precise numbers never really revealed. Here we have the body and not the machine–not the bicycle weight for a won-by-the-split-second time trial. Would it be different if dancers disclosed their weight readily before their seasons at respective theaters the way one can weigh a bicycle? Would the mystery of dancers fine tuning dissolve–a 5’6″ dancer would know definitively where she stood compared to her peers at one weight or another? Less easily unveiled is the impossibility of endless hours of class that are kept behind the scenes. Daily class can’t be as easily boiled down to a number or metric. It is simply difficult and challenging, everyday. We know about this ritual of class, but few ever really get a look at it or can actually comprehend that this is everyday life for a dancer. To do it takes a certain unstoppable-ness, the just short of ridiculous kind.

At the end of Giselle, the lover wakes by Giselle’s grave stone and it has been perhaps all a dream to him, except that Giselle is still dead. We wake everyday to our own limits, from the dream that we might be like Giselle or Simpson, unstoppable. Lest we forget, there is the jolting reality of one and the dream-like illusion of another to remind us. Emily Gresh